Donald Trump’s election has been widely criticized as frighteningly similar to the rise of Nazism in the 1930s and Trump with Hitler himself. I’ve written that the two events are not totally congruent, the main difference being the contrast between a collapsed economy in Germany and a thriving one here (although Trump conned his supporters into believing otherwise). In the end, however, Hitler’s extremism, propelled by his messianic vision, hurtled his country to ruin, as Trump, chiefly because of his own bloated ego, threatens to do to ours.

There are an unfortunate number of alarming and depressing parallels between their behavior and outlooks, enough so that it is not unfair to speculate whether one is an admirer of the other. I encountered two of those parallels this week in Paris, which were made all the more jarring for being right in front of me.

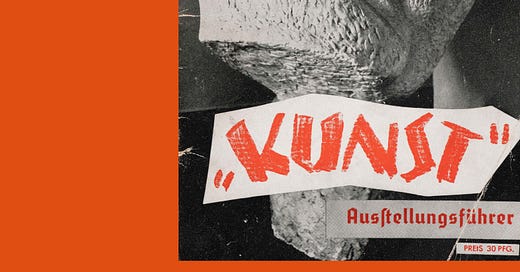

Currently, at the Picasso Museum, there is an extraordinary exhibit, “Degenerative Art: Modern Art on Trial Under the Nazis.” The focus is a “propaganda exhibition "Entartete Kunst" (degenerate art), held in Munich in 1937, which showed over 600 works by around a hundred artists representing the different currents of modern art, from Otto Dix to Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, from Vassily Kandinsky to Emil Nolde, from Paul Klee to Max Beckmann, in a setting designed to provoke the disgust of the public.” The exhibition ranges from Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933, through an auction in which the Nazis realized they could rake in large sums of money from selling works they had stolen and originally vowed to destroy, to a determination after the war by whoever had the art in their possession to hang on to the loot.

While the work in the current exhibition, which includes paintings by Van Gogh, Chagall, and Picasso, among many, many others, is brilliant, it is merely a backdrop to the political story and it is there that the impact is most deeply felt.

From the very start, it is obvious how the aspirations of these two terrible men and their visions of themselves as leaders eerily coincide.

Hitler saw himself as the modern incarnation of a Roman emperor. Just inside the entrance, the most astounding film is running. It depicts a procession at which Hitler is reviewing an immense parading column of worshipful Germans. Rolling in front of him are two-story high sculptures of eagles and warriors on horseback, and even oar-driven galleys, flanked by men bearing Roman pennants and nubile, toga-clad maidens. Hitler stands among his minions, smiling blissfully, quite obviously seeing himself as leading Germany to his vision of grandeur and glory

One could easily imagine Trump reviewing a similar exhibition and enjoying it equally.

To attain his vision, Hitler pursued, with determination and delight, a purge of any influence—artistic, intellectual, legal, and political—which might interfere with its actualization, as Trump is now engaged in as well. While Hitler initiated a campaign where “more than 1,400 artists were abused, exposed to public humiliation, dismissed from teaching positions, banned from exhibiting and working, subjected to physical threats and forced into exile,” Trump has used the power of the federal government to strip rights and privileges from groups that he considers inferior or degenerate, especially those who are transgender, but also Blacks, Latinos, and Native Americans. What Hitler did with violence and imprisonment, Trump is doing using a financial bludgeon and a corrupted justice department, while also asserting de facto control over higher education and major law firms and perverting public education by executive fiat.

Although there have been no reports of those considered heterodox being beaten in the streets or their property vandalized, it seems inevitable that there will be. And nothing would please Trump more than if his enemies decided to leave the United States.

The other example is a permanent installation on Île de la Cité, in the shadow of the rebuilt Nôtre Dame called “The Memorial to the Martyrs of the Deportation,” French victims of the Nazi death camps. Opened in 1962 by Charles De Gaulle, it is set up to make visitors walk through a series of brown metal walls with the feel of a prison, leading to the crypt where the remains of an unknown deportee are held.

The French may celebrate the Resistance, but they do not shrink from the role their own people played in aiding the Nazis to murder 200,000 innocent French citizens. In other words, they do not deny their history but use it as a means to learn and grow, so the outrages of the past are not repeated in the future. There is thus a tacit understanding that denying history or trying to change or distort it is a dangerous undertaking.

Donald Trump does not agree. From his attempt to erase Jackie Robinson’s rebellion against racism as a lieutenant in the United States Army to his takeover of both the Kennedy Center and the Smithsonian, he is intent on rewriting history as the white-centric, we’re-great-and-never-made-a-mistake narrative that the nation abandoned more than a half-century ago.

As an historian, I am acutely aware of the pitfalls of this sort of, well, white-washing, of a country’s past, as are the French who lived through it and Germans who perpetrated it.

Europe is not perfect, certainly, and they dislike their leaders as much as anyone else, perhaps more, but there is a respect for the past that the United States now seems to lack. They also have serious immigration problems and widespread racism to deal with but have so far resisted the call of the far right.

Being here, away from what has begun to be daily, perhaps hourly, reminders of America’s descent from the beacon of freedom and equal justice it once was to what it seems to have become is both a relief and depressing. (And this is to in no way to deny the profound injustices rife in our own history.)

One can also not escape the feeling that Europe, with the exception of Hungary, has repelled a return to its more sordid past because they had experience with what fascism, even the warmed-over variety being offered by the likes of Marine Le Pen, truly represents. So far, we have not.

It took a war and the destruction of Germany to get rid of Hitler. One can only hope that, despite all indications to the contrary, there is still a sufficient reservoir of fundamental decency in our nation to achieve that goal with the United States still more or less intact.

That memorial on the Ile de Citie is a beautiful rendering of a terrible series of events. Juts as only smart people can recognize when they've done something stupid, only countries led be people of honor can recognize shameful acts of the past.